Understanding M47.816 – Lumbar Spondylosis Without Myelopathy or Radiculopathy

Lumbar spondylosis, classified under ICD-10 code M47.816, refers to degenerative changes in the lumbar spine without myelopathy or radiculopathy. This condition primarily affects the lower back, causing chronic pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility due to progressive wear and tear of intervertebral discs and facet joints. Unlike cases involving nerve root compression (radiculopathy) or spinal cord involvement (myelopathy), M47.816 is limited to localized degeneration, meaning that while discomfort and stiffness are common, it does not initially result in radiating pain, numbness, or neurological deficits (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

The prevalence of lumbar spondylosis increases with age, with studies indicating that over 80% of individuals over 40 exhibit some degree of spinal degeneration, even if asymptomatic (Kumar 2019). However, lifestyle factors, including poor posture, sedentary behavior, repetitive spinal stress, and excess body weight, can accelerate degeneration, leading to functional limitations and chronic discomfort at an earlier age.

While conservative treatments—such as physical therapy, pain management strategies, ergonomic adjustments, and dietary interventions—form the first line of treatment, some individuals may require interventional procedures like corticosteroid injections or facet joint radiofrequency ablation for symptom relief. Additionally, alternative and complementary therapies, including Ayurveda, Siddha medicine, yoga, and herbal supplements such as liposomal curcumin, have shown promise in reducing inflammation and improving spinal function (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of M47.816, covering its causes, symptoms, diagnostic methods, treatment options, and preventive strategies. By understanding the nature of lumbar spondylosis and the latest advancements in both conventional and alternative treatments, individuals can take proactive steps to manage symptoms, slow disease progression, and enhance overall spinal health.

What Does Diagnosis Code M47.816 Mean?

Understanding M47.816 as an ICD-10 Code

M47.816 is a medical classification under the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) that refers to spondylosis without myelopathy or radiculopathy in the lumbar region. Spondylosis is a broad term describing degenerative changes in the spine, including osteoarthritis of the vertebrae, intervertebral disc wear, and bone spur formation. In the context of M47.816, these degenerative changes occur in the lumbar spine—the lower back portion of the vertebral column—but do not involve nerve root compression (radiculopathy) or spinal cord dysfunction (myelopathy) (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

This diagnosis is common among middle-aged and older adults due to natural aging and spinal wear. However, younger individuals with a history of repetitive spinal stress, poor posture, or previous spinal injuries may also develop lumbar spondylosis (Kumar et al. 2019). Patients with M47.816 may experience lower back stiffness, discomfort, and reduced mobility, but since myelopathy and radiculopathy are absent, they generally do not suffer from severe neurological deficits such as numbness, weakness, or radiating pain (Kumar et al. 2019).

Differences Between Spondylosis With and Without Myelopathy/Radiculopathy

Spondylosis can be classified based on whether it leads to nerve compression or spinal cord involvement:

- Spondylosis Without Myelopathy or Radiculopathy (M47.816)

- Degenerative changes occur in the lumbar spine.

- Patients typically experience chronic lower back pain and stiffness but do not have nerve-related symptoms like shooting pain, tingling, or muscle weakness.

- Pain is usually localized and worsens with prolonged activity or poor posture but does not radiate to the legs.

- Treatment is often conservative, including physical therapy, posture correction, and pain management techniques (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

- Spondylosis With Radiculopathy (M47.26, M47.2X)

- Degenerative changes lead to nerve root compression, commonly affecting the sciatic nerve.

- Patients may experience radiating pain down the legs (sciatica), tingling, numbness, and muscle weakness.

- Symptoms worsen with activities that increase spinal pressure, such as prolonged sitting or bending.

- Treatments may include nerve block injections, anti-inflammatory medications, and, in severe cases, spinal decompression surgery (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

- Spondylosis With Myelopathy (M47.1X)

- This condition affects the spinal cord, typically in the cervical or thoracic region.

- Patients may develop difficulty walking, loss of hand coordination, muscle weakness, and bladder or bowel dysfunction.

- Symptoms are more severe than radiculopathy and may require surgical intervention if the spinal cord is compressed.

Why the Distinction Matters

Proper classification of spondylosis is crucial for diagnosing and treating spinal degeneration. While M47.816 can often be managed through non-invasive treatments, radiculopathy or myelopathy may require more aggressive interventions to prevent long-term disability. Understanding the differences in symptoms and progression helps healthcare providers tailor effective treatment strategies based on the severity of spinal degeneration (Kumar et al. 2019).

Causes and Risk Factors of Lumbar Spondylosis

Aging and Natural Spinal Degeneration

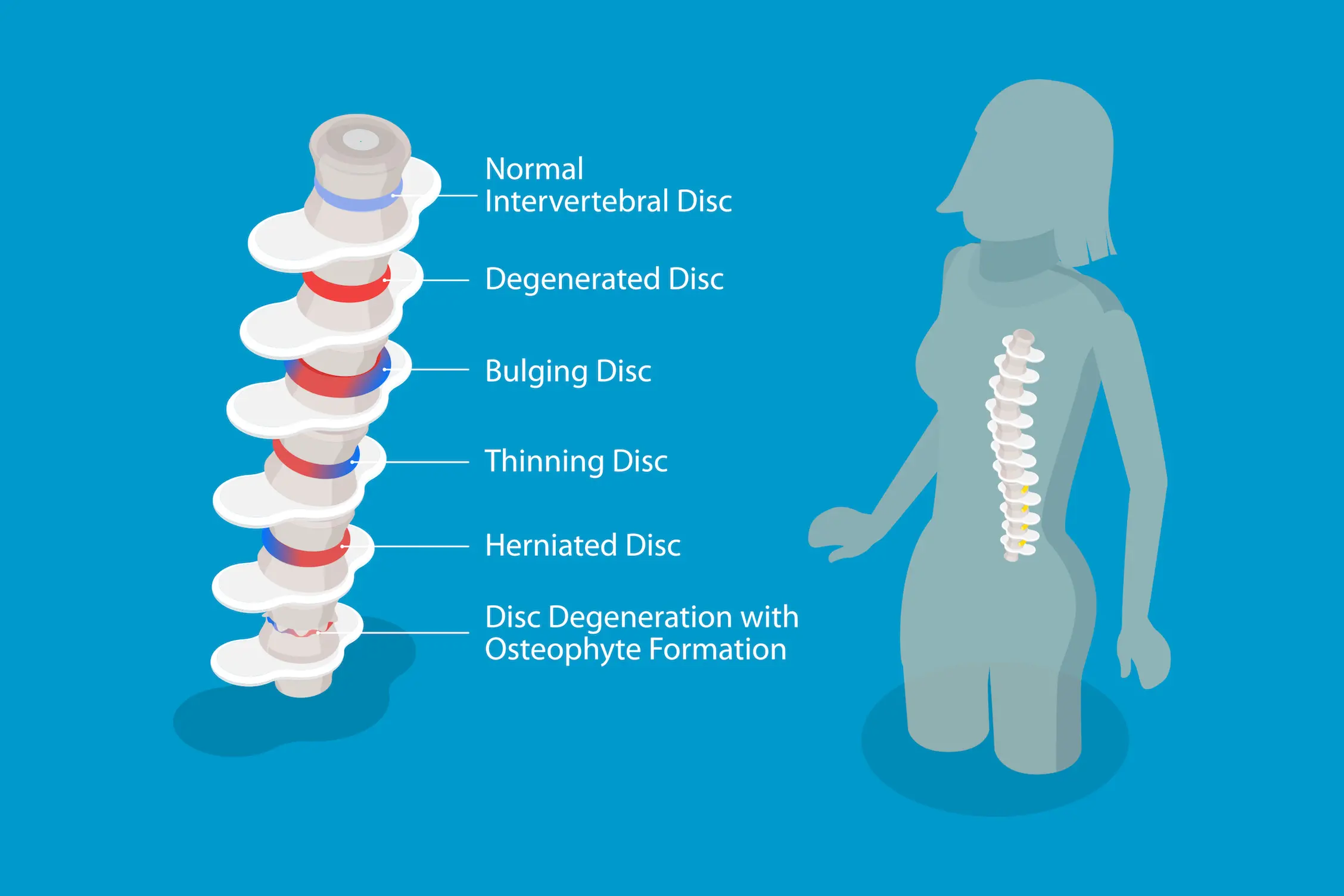

One of the primary causes of lumbar spondylosis is the natural aging process, which leads to progressive degeneration of the spinal discs, vertebral joints, and surrounding structures. As individuals age, the intervertebral discs lose hydration and elasticity, reducing their ability to absorb shock and resulting in disc thinning and collapse (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024). This degeneration increases the mechanical stress on the facet joints, contributing to the formation of osteophytes (bone spurs), which may further restrict movement and exacerbate pain (Kumar et al. 2019). Studies indicate that over 80% of individuals over the age of 40 show some degree of lumbar spondylosis on imaging, even if they remain asymptomatic (Kumar et al. 2019).

Genetic Predisposition

Genetic factors also play a significant role in the development of lumbar spondylosis. Research suggests that individuals with a family history of degenerative disc disease are at a higher risk of experiencing early-onset spinal deterioration. Variations in genes related to collagen production, inflammatory responses, and bone metabolism have been linked to increased susceptibility to intervertebral disc degeneration (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024). Additionally, certain hereditary spinal conditions, such as Scheuermann’s disease or congenital spinal stenosis, may predispose individuals to early degenerative changes in the lumbar spine.

Lifestyle Factors: Posture, Physical Activity, and Occupation

Daily habits and occupational activities significantly influence spinal health. Poor posture, such as prolonged sitting with improper lumbar support, can accelerate disc degeneration and misalignment of the vertebrae (Kumar et al. 2019). Jobs that require repetitive lifting, bending, or twisting—such as construction work, nursing, and warehouse labor—place excessive strain on the lower back, leading to faster joint deterioration (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024). Conversely, a sedentary lifestyle with minimal physical activity weakens core muscles, reducing spinal stability and increasing the likelihood of spondylotic changes.

Other Contributing Conditions (e.g., Arthritis, Previous Spinal Injuries)

Certain medical conditions and past injuries can also accelerate lumbar spondylosis. Osteoarthritis, a degenerative joint disease, often affects the facet joints in the spine, leading to inflammation, stiffness, and reduced range of motion (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024). Rheumatoid arthritis, though less common in the lumbar spine, can contribute to joint erosion and instability. Previous spinal injuries, such as fractures or herniated discs, can disrupt normal spinal alignment, leading to compensatory stress on adjacent vertebrae and accelerating degeneration (Kumar et al. 2019). Additionally, metabolic disorders such as osteoporosis can weaken vertebral bones, making them more susceptible to structural collapse and degenerative changes.

Understanding these underlying causes and risk factors is crucial for early prevention and effective management of lumbar spondylosis. By addressing lifestyle habits, maintaining proper posture, and seeking early medical intervention, individuals can slow down the progression of spinal degeneration and reduce their risk of chronic back pain and disability.

Symptoms of M47.816

What Are the Symptoms of Lumbar Spondylosis Without Myelopathy?

Lumbar spondylosis without myelopathy (M47.816) presents as a degenerative condition affecting the lower back, primarily due to age-related wear and tear of the intervertebral discs and facet joints. Unlike conditions involving nerve compression, this form of spondylosis does not lead to spinal cord damage or significant nerve root involvement. However, individuals diagnosed with M47.816 often experience chronic lower back discomfort and mobility issues.

Chronic Lower Back Pain

One of the hallmark symptoms of M47.816 is persistent lower back pain that gradually worsens over time. This discomfort is typically localized to the lumbar spine and does not radiate into the legs, differentiating it from conditions like lumbar radiculopathy (Kumar 2019). The pain is dull and aching in nature, often exacerbated by prolonged standing, sitting, or repetitive movements involving the lower back.

Stiffness and Reduced Flexibility

Due to the degenerative changes in the lumbar vertebrae, affected individuals often experience morning stiffness or stiffness after periods of inactivity (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024). This rigidity can limit range of motion, making it difficult to perform everyday activities such as bending forward, twisting, or extending the spine. Over time, spinal stiffness may contribute to postural changes and an increased risk of developing compensatory musculoskeletal issues.

Pain Aggravation with Movement

Individuals with M47.816 often report that certain movements trigger or worsen their pain. Activities such as lifting heavy objects, prolonged standing, or bending forward may place additional stress on the lumbar spine, intensifying discomfort. Unlike conditions with nerve involvement, pain in M47.816 is typically mechanical, meaning it subsides with rest and worsens with excessive strain (Kumar 2019).

No Radiating Nerve Pain (Differentiating from Radiculopathy)

A key distinguishing feature of M47.816 is the absence of radiating pain into the legs or feet. In contrast, lumbar radiculopathy (M47.26) occurs when nerve roots become compressed, leading to shooting pain, numbness, or weakness in the lower extremities. Because M47.816 does not involve direct nerve impingement, individuals typically experience localized back pain without neurological deficits (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

How is M47.816 Different from Other Spinal Conditions?

Several spinal conditions share symptoms with lumbar spondylosis, but key differences help distinguish M47.816 from related disorders.

Comparison with Radiculopathy (M47.26 – Spondylosis with Radiculopathy)

- M47.816 (Spondylosis Without Radiculopathy):

- Localized lower back pain and stiffness.

- No nerve compression, meaning no radiating pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs.

- Pain is mechanical, worsening with movement but improving with rest.

- M47.26 (Spondylosis With Radiculopathy):

- Involves nerve root compression, causing radiating pain (sciatica), tingling, or leg weakness.

- May lead to difficulty walking or standing for long periods.

- Often requires more aggressive treatments, including epidural injections or surgery (Kumar 2019).

Differences Between Lumbar Facet Syndrome and Spondylosis

Lumbar facet syndrome and spondylosis share similar symptoms, but their underlying causes differ:

- Lumbar Facet Syndrome:

- Caused by degeneration or inflammation of the facet joints.

- Pain is sharp and localized, often worsening with spinal extension or prolonged standing.

- Commonly managed with facet joint injections and anti-inflammatory treatments.

- Lumbar Spondylosis (M47.816):

- A broader degenerative condition affecting discs, joints, and ligaments.

- Pain is typically dull and aching, with progressive stiffness over time.

- Managed with physical therapy, lifestyle modifications, and pain relief strategies (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Understanding Lumbar Spondylolisthesis vs. Spondylosis

While lumbar spondylosis refers to degenerative changes, lumbar spondylolisthesis occurs when a vertebra slips forward over the one below it, often due to fractures or instability. Key differences include:

- Spondylosis (M47.816):

- Primarily involves joint and disc degeneration.

- Pain remains localized, with no vertebral slippage.

- Spondylolisthesis:

- Can cause nerve compression, leading to leg pain, weakness, and instability.

- Often requires bracing or surgical intervention if severe (Kumar 2019).

By understanding these distinctions, healthcare providers can diagnose and treat M47.816 more effectively, helping patients manage pain and maintain spinal health.

Diagnosis of Lumbar Spondylosis (M47.816)

Clinical Examination and Patient History

The diagnosis of lumbar spondylosis (M47.816) begins with a comprehensive clinical evaluation, where healthcare providers assess the patient’s symptoms, medical history, and physical condition. Patients with M47.816 often report chronic lower back pain, stiffness, and reduced flexibility, which worsens with prolonged standing, sitting, or certain movements. Unlike cases involving radiculopathy, patients with M47.816 do not experience radiating nerve pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

During the physical examination, doctors perform tests to assess spinal mobility, posture, and pain response to movement. Common clinical assessments include:

- Palpation of the lumbar spine to check for tenderness and muscle tightness.

- Range of motion testing to evaluate limitations in spinal flexion, extension, and rotation.

- Straight leg raise (SLR) test to rule out nerve involvement, which should be negative in M47.816 cases (Kumar 2019).

- Neurological evaluation to ensure that there are no signs of nerve compression, such as sensory loss or muscle weakness.

Imaging Tests Used for Diagnosis

To confirm the diagnosis of M47.816, doctors rely on imaging studies that visualize degenerative changes in the lumbar spine. These tests help differentiate spondylosis without myelopathy or radiculopathy from other spinal disorders.

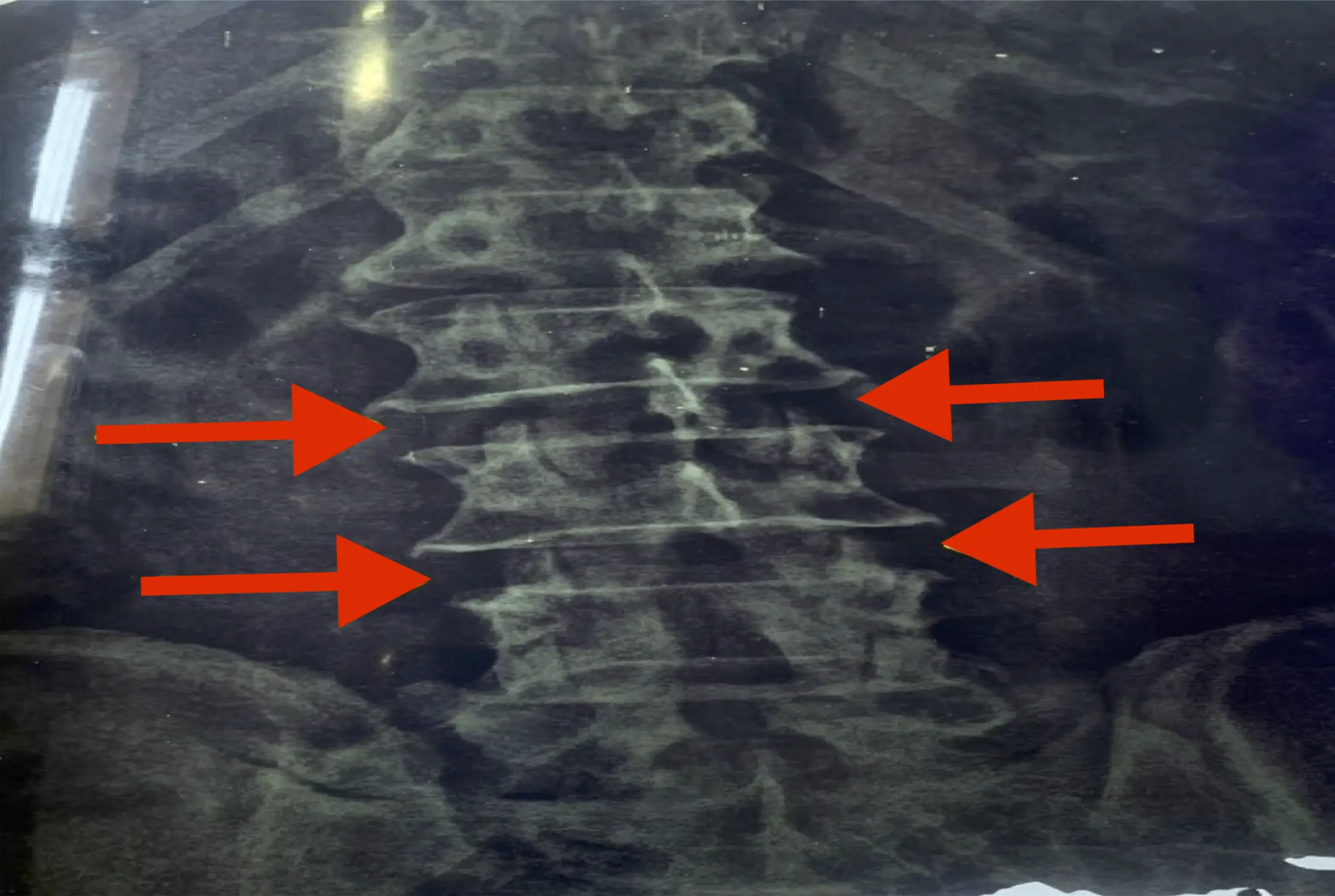

X-ray

A lumbar spine X-ray is the first-line imaging test for detecting bony abnormalities. It can reveal:

- Loss of disc height, indicating degeneration.

- Osteophyte (bone spur) formation, common in lumbar spondylosis.

- Facet joint degeneration, which contributes to stiffness and pain.

While X-rays are effective for evaluating bone structure, they do not provide detailed information on soft tissues, nerves, or intervertebral discs (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

For a more detailed assessment, an MRI scan is recommended, especially if severe symptoms persist despite conservative treatment. MRI provides high-resolution images of spinal discs, nerves, and soft tissues, helping to:

- Identify disc degeneration and dehydration.

- Assess for spinal stenosis or hidden nerve compression.

- Rule out conditions that mimic spondylosis, such as herniated discs or infections (Kumar 2019).

CT Scan (Computed Tomography)

A CT scan is useful for cases where an MRI is unavailable or contraindicated (such as in patients with metal implants). CT scans offer detailed cross-sectional images of bone structures, making them ideal for assessing:

- Bone spur formation and facet joint hypertrophy.

- Calcification within spinal ligaments.

- Spinal alignment abnormalities (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Role of Differential Diagnosis

Since M47.816 shares symptoms with many other spinal conditions, a differential diagnosis is crucial to rule out alternative causes of lower back pain.

Ruling Out Spinal Stenosis

- Spinal stenosis involves the narrowing of the spinal canal, which can compress nerves.

- Unlike M47.816, patients with spinal stenosis experience numbness, weakness, or leg pain (neurogenic claudication) when walking, which improves when sitting.

- MRI or CT scans are needed to confirm stenosis vs. spondylosis (Kumar 2019).

Distinguishing from Herniated Discs

- A herniated disc occurs when the inner disc material protrudes and compresses nearby nerves.

- Unlike M47.816, herniated discs typically cause sharp, radiating pain (sciatica), numbness, or tingling down the legs.

- MRI is the best diagnostic tool to differentiate herniation from degenerative spondylosis (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Excluding Other Spinal Conditions

Other conditions that may mimic M47.816 include:

- Lumbar facet joint syndrome (pain localized to the lower back but worsens with extension).

- Osteoarthritis of the spine (involves widespread joint degeneration).

- Spondylolisthesis (vertebral slippage causing instability).

- Inflammatory conditions like ankylosing spondylitis (morning stiffness, positive HLA-B27 marker) (Kumar 2019).

A combination of clinical examination, imaging studies, and differential diagnosis ensures an accurate diagnosis of M47.816, allowing for proper treatment planning and symptom management.

Treatment Options for M47.816 – Lumbar Spondylosis

The management of M47.816 – lumbar spondylosis without myelopathy or radiculopathy involves a combination of conservative treatments, interventional procedures, and, in severe cases, surgical interventions. The choice of treatment depends on the severity of symptoms, functional impairment, and response to non-invasive approaches.

Conservative Treatment Options

Physical Therapy: Stretching and Strengthening Exercises

Physical therapy is a cornerstone of conservative treatment, focusing on improving spinal flexibility, core strength, and posture. Stretching exercises help alleviate stiffness and maintain a full range of motion, while strengthening exercises target the core, back, and pelvic muscles to support spinal stability (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024). Specific therapeutic exercises such as lumbar extensions, pelvic tilts, and hamstring stretches have been shown to reduce lower back pain and prevent further degeneration.

Pain Management: NSAIDs and Muscle Relaxants

For individuals experiencing persistent lower back pain, medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly prescribed to reduce inflammation and discomfort. Drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen help control mild to moderate pain, while muscle relaxants like cyclobenzaprine may be used for patients with muscle spasms associated with lumbar spondylosis (Kumar 2019). Additionally, some studies suggest that liposomal curcumin, a bioavailable form of curcumin, has anti-inflammatory properties that may provide pain relief and improve spinal function (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Posture Correction: Ergonomic Adjustments

Poor posture is a significant contributing factor to lumbar spondylosis progression. Ergonomic adjustments, such as using lumbar support cushions, adjustable workstations, and standing desks, can reduce excess pressure on the spine. Patients are encouraged to maintain a neutral spine position while sitting and avoid prolonged periods of hunching over devices or desks (Kumar 2019).

Lifestyle Modifications: Weight Management, Diet, and Activity Adjustments

Excess body weight places additional stress on the lumbar spine, accelerating disc degeneration. Weight management through a balanced diet and regular exercise can help reduce strain on the lower back (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024). Incorporating anti-inflammatory foods such as liposomal curcumin supplements, omega-3 fatty acids, and antioxidants may also contribute to pain reduction and improved spinal health (Kumar 2019).

Interventional Treatments for Severe Cases

Corticosteroid Injections for Inflammation

For patients whose symptoms persist despite conservative measures, corticosteroid injections may be administered directly into the lumbar facet joints or epidural space. These injections provide temporary relief from inflammation and pain, often lasting several weeks to months. However, repeated steroid use should be approached cautiously due to potential side effects such as cartilage degeneration (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Facet Joint Injections and Radiofrequency Ablation

Facet joint injections deliver a combination of local anesthetics and corticosteroids directly into the affected spinal joints, offering pain relief for individuals experiencing facet joint-related lumbar spondylosis. If the pain recurs, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) may be considered. RFA uses heat energy to disrupt pain signals by targeting the sensory nerves supplying the facet joints. Studies indicate that RFA can provide long-lasting relief, ranging from six months to two years (Kumar 2019).

Minimally Invasive Procedures (If Pain Persists)

When non-surgical approaches fail, patients may undergo minimally invasive procedures such as percutaneous decompression or laser-assisted discectomy. These procedures remove damaged disc material and reduce nerve irritation while preserving as much of the spinal structure as possible (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Surgical Intervention (As a Last Resort)

When Surgery is Considered

Surgery is not typically required for M47.816, as it does not involve nerve compression or myelopathy. However, surgery may be considered for patients who develop spinal instability, severe chronic pain unresponsive to treatment, or worsening functional impairment. Individuals who fail to improve after six months or more of non-invasive treatments may be evaluated for surgical intervention (Kumar 2019).

Common Surgical Procedures (e.g., Spinal Fusion, Laminectomy)

The two most common surgical options for lumbar spondylosis include:

- Spinal Fusion: This procedure stabilizes the spine by fusing two or more vertebrae with bone grafts and implants. While effective in reducing pain caused by spinal instability, fusion can limit spinal flexibility and increase stress on adjacent segments.

- Laminectomy (Decompression Surgery): In cases where bone spurs or thickened ligaments contribute to spinal stenosis, a laminectomy may be performed to remove excess bone and relieve pressure on the spinal canal.

Surgical interventions are typically reserved for severe, disabling cases and are followed by postoperative rehabilitation to restore mobility and strength.

By tailoring treatment strategies to individual patient needs, a combination of conservative, interventional, and, if necessary, surgical options can effectively manage M47.816 and improve quality of life.

Alternative and Complementary Therapies

Ayurveda-Based Treatment for Lumbar Spondylosis (From Research Studies)

Ayurveda, an ancient system of medicine, has been widely studied for its effectiveness in managing lumbar spondylosis. A case study by Kulkarni and Parwe (2024) demonstrated significant pain relief and improved mobility in a patient who underwent Ayurvedic therapies for chronic lower back pain. The treatment protocol included Panchakarma-based interventions, focusing on detoxification and restoration of spinal health.

Niruha Basti & Anuvasan Basti for Pain Relief

One of the core Ayurvedic treatments for lumbar spondylosis is Basti therapy, an enema-based intervention that helps reduce inflammation and promote joint lubrication. The study reported that the combination of Niruha Basti (medicated decoction enema) and Anuvasan Basti (oil-based enema) provided substantial pain relief. These treatments are believed to work by flushing out toxins and rebalancing the Vata dosha, which is primarily responsible for degenerative spinal disorders (Kulkarni & Parwe 2024). Research also suggests that liposomal curcumin, due to its enhanced bioavailability, may serve as an adjunct to Basti therapy, amplifying its anti-inflammatory effects and improving long-term outcomes in spondylosis patients.

Massage Therapy & Herbal Applications

Massage therapy, or Abhyanga, is another integral component of Ayurvedic management for lumbar spondylosis. Therapeutic oils infused with medicinal herbs such as Dashmool, Mahanarayan oil, and Bala oil are used to alleviate stiffness and improve circulation in the lumbar region (Kulkarni & Parwe 2024). Additionally, heat therapy (Swedana), often administered alongside massage, enhances muscle relaxation and facilitates deeper penetration of medicinal compounds. Some Ayurvedic formulations, including those containing liposomal curcumin, have demonstrated promising results in reducing oxidative stress and mitigating chronic pain associated with lumbar spondylosis.

Results: Significant Pain Reduction and Improved Mobility

The case study reported a dramatic decrease in pain levels, with a reduction in the Oswestry Disability Index score from 49 to 18 after a nine-day Ayurvedic treatment program (Kulkarni & Parwe 2024). Patients also exhibited improved spinal flexibility and enhanced quality of life. These findings highlight the potential of Ayurveda as a complementary approach to conventional treatments, particularly for individuals seeking non-surgical options for managing M47.816.

Yoga and Siddha Medicine for Lumbar Spondylosis

Effect of Yoga Postures (Asana) & Pranayama in Pain Management

Yoga has been widely recognized as an effective therapy for managing lumbar spondylosis. Kumar (2019) conducted a study evaluating the impact of yogic postures (asana) and controlled breathing techniques (pranayama) on patients with chronic lumbar pain. The findings revealed that targeted yoga interventions significantly improved spinal flexibility, alleviated muscle tension, and enhanced overall mobility.

Postures such as Bhujangasana (Cobra Pose), Pawanmuktasana (Wind-Relieving Pose), and Marjaryasana-Bitilasana (Cat-Cow Pose) were particularly effective in promoting spinal decompression and strengthening the lower back. Additionally, Anulom-Vilom Pranayama (alternate nostril breathing) was found to reduce stress-induced muscular tension and enhance oxygenation of spinal tissues (Kumar 2019). Emerging research suggests that integrating liposomal curcumin into a yoga-based therapy plan may provide enhanced anti-inflammatory benefits, further aiding in pain relief and mobility restoration.

Siddha Herbal Treatments & External Applications

Siddha medicine, a traditional healing system from South India, also offers promising approaches for treating lumbar spondylosis. Herbal formulations such as Thriphala oil, Murukkan vithai pills, and Thrikadugu chooranam are commonly prescribed for their analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties (Kumar 2019). External applications, including oil massages with Sivappu Kukkil Thailam, have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing stiffness and nerve-related discomfort.

The Siddha approach integrates both internal and external therapies, addressing not only the physical manifestations of spondylosis but also underlying imbalances in bodily energies (Doshas). This holistic approach is particularly beneficial for patients experiencing nerve compression or radiating pain in the lower extremities. Recent studies suggest that supplementing Siddha treatments with bioavailable compounds like liposomal curcumin may enhance pain modulation and provide long-lasting relief (Kumar 2019).

Outcomes: Improved Flexibility and Decreased Pain Intensity

Patients who followed a structured Siddha and yoga regimen experienced notable improvements in spinal flexibility and pain reduction. The study recorded a decrease in the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain score from 8 to 2 after 40 days of consistent practice, along with increased mobility and reduced stiffness (Kumar 2019). These findings suggest that combining Siddha therapies with yoga can serve as an effective, non-invasive alternative for managing M47.816.

Related ICD-10 and ICD-9 Codes for M47.816

Medical coding plays a crucial role in diagnosing, documenting, and treating lumbar spondylosis. M47.816, classified under ICD-10-CM, specifically refers to spondylosis without myelopathy or radiculopathy in the lumbar region. However, various related ICD codes exist for different manifestations of spinal degeneration. Understanding these related codes helps ensure accurate billing, treatment planning, and effective management of spinal conditions.

What Are the Related ICD-10 Codes?

Several ICD-10 codes are closely related to M47.816, each describing different variations of spinal degeneration and associated complications:

M47.26 – Spondylosis with Radiculopathy

This code is used when degenerative changes in the lumbar spine lead to radiculopathy, which occurs when nerve roots are compressed, causing radiating pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs. Unlike M47.816, which is limited to localized lower back pain and stiffness, M47.26 involves nerve impingement, leading to symptoms like sciatica or difficulty walking (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

M47.2 – Other Spondylosis with Radiculopathy

This broader classification includes spondylotic changes in any spinal region (cervical, thoracic, or lumbar) that cause radiculopathy. Like M47.26, it indicates that nerve root compression is present, distinguishing it from M47.816, which involves degeneration without nerve involvement (Kumar 2019).

M54.5 – Low Back Pain (Often Coexisting with M47.816)

Low back pain (M54.5) is one of the most common symptoms associated with lumbar spondylosis and is frequently coded alongside M47.816 when pain is the primary clinical complaint. While M47.816 specifies structural degeneration, M54.5 is a symptom-based code that captures generalized lower back pain without specifying the underlying pathology (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

What is the ICD-9-CM Code for M47.816?

Transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 for Lumbar Spondylosis

Before the adoption of ICD-10 in 2015, lumbar spondylosis was classified under ICD-9-CM, a coding system that contained fewer diagnostic categories and less specificity compared to ICD-10. Under the previous system, lumbar spondylosis did not have a distinct code differentiating cases with and without nerve involvement, which often led to broader, less precise coding practices (Kumar 2019).

Former Classification of Lumbar Degenerative Diseases

In ICD-9-CM, the most commonly used codes for lumbar spondylosis and related conditions included:

- 721.3 – Lumbosacral Spondylosis Without Myelopathy

- Equivalent to M47.816 in ICD-10.

- Used for cases where degenerative changes were present without significant spinal cord or nerve root involvement.

- 722.52 – Degeneration of Lumbar or Lumbosacral Intervertebral Disc

- Applied when disc degeneration contributed to spinal deterioration.

- Comparable to ICD-10 codes for intervertebral disc disorders.

- 724.2 – Lumbago (Lower Back Pain)

- A general classification for non-specific lower back pain, similar to M54.5 in ICD-10.

The transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 provided greater clarity in distinguishing degenerative lumbar conditions with and without nerve involvement, allowing for more precise treatment planning and documentation (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

By understanding the historical and current classifications, healthcare providers can ensure accurate coding, which is essential for proper diagnosis, treatment selection, and insurance reimbursement for lumbar spondylosis (M47.816).

Preventive Measures for Lumbar Spondylosis

Preventing lumbar spondylosis (M47.816) requires a proactive approach that focuses on spinal health, posture correction, ergonomic adjustments, and nutritional support. Since lumbar spondylosis results from age-related degeneration and lifestyle factors, incorporating preventive strategies can significantly reduce the risk of chronic back pain and functional limitations.

Best Practices for Spine Health

Maintaining a healthy spine involves a combination of proper posture, regular exercise, and spinal alignment awareness. Engaging in low-impact exercises such as swimming, yoga, and Pilates helps improve core strength, spinal flexibility, and overall posture stability (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

- Core Strengthening: Strengthening the abdominal and back muscles provides better spinal support and prevents excessive strain on the lumbar vertebrae. Exercises such as planks, pelvic tilts, and bridges enhance spinal alignment.

- Stretching & Mobility Work: Regular lumbar stretches, hamstring flexibility exercises, and spinal twists improve range of motion and reduce stiffness associated with lumbar spondylosis (Kumar 2019).

- Weight Management: Excess body weight increases stress on the lumbar spine, accelerating disc degeneration. Maintaining a healthy weight through balanced nutrition and regular physical activity lowers the risk of spondylotic changes.

Additionally, incorporating liposomal curcumin into daily wellness routines may help reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, both of which contribute to spinal degeneration. Curcumin’s bioavailability is significantly enhanced in liposomal form, making it a promising natural supplement for long-term spinal health (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Workplace Ergonomics & Lumbar Support

Sedentary work environments often contribute to poor posture, spinal misalignment, and chronic lower back pain. Proper ergonomic adjustments can significantly reduce the risk of developing lumbar spondylosis and help individuals maintain a healthy spine throughout their careers.

- Ergonomic Chair & Lumbar Support: Using a chair with proper lumbar support helps maintain the spine’s natural curvature. Adjustable seat height, backrests, and armrests reduce strain on the lower back (Kumar 2019).

- Standing Desks & Movement Breaks: Alternating between sitting and standing reduces prolonged stress on the lumbar spine. Incorporating frequent movement breaks, stretching, and standing desk options can prevent spinal stiffness and disc compression.

- Monitor & Desk Positioning: Computer screens should be positioned at eye level, and keyboards should be aligned to prevent hunching forward, which can place excessive strain on the lumbar spine and cervical region.

Workers in physically demanding jobs should also prioritize proper lifting techniques, including bending at the knees rather than the waist, keeping objects close to the body, and avoiding twisting movements that strain the lumbar vertebrae (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Role of Diet & Supplements (Vitamin D, Omega-3s)

Proper nutrition plays a critical role in supporting spinal health, bone density, and joint function. Key nutrients such as Vitamin D, calcium, and Omega-3 fatty acids are essential in preventing spinal degeneration and managing inflammation associated with lumbar spondylosis.

- Vitamin D & Calcium:

- Essential for bone density and vertebral strength.

- Deficiencies in Vitamin D have been linked to increased risk of spinal disc degeneration and chronic back pain (Kumar 2019).

- Sources include fatty fish, fortified dairy products, and sunlight exposure.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids:

- Found in fish oil, flaxseeds, and walnuts, Omega-3s have potent anti-inflammatory properties.

- Regular intake can help reduce spinal inflammation, joint stiffness, and chronic pain.

- Liposomal Curcumin:

- As an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compound, curcumin reduces oxidative stress in spinal tissues.

- Liposomal formulations enhance bioavailability, making it a more effective option for spinal health support (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

By integrating nutritional strategies, ergonomic habits, and spine-strengthening exercises, individuals can effectively prevent lumbar spondylosis and maintain a healthy, pain-free back well into later years.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on M47.816

What is Facet Syndrome and How is it Related to M47.816?

Facet syndrome is a degenerative condition affecting the facet joints, which are the small stabilizing joints between each vertebra. These joints are responsible for maintaining spinal flexibility while preventing excessive movement. Over time, wear and tear can cause cartilage breakdown, joint inflammation, and pain, leading to facet syndrome (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Facet syndrome is closely related to M47.816 (lumbar spondylosis without myelopathy or radiculopathy) because both conditions involve spinal degeneration. Patients with M47.816 may develop facet joint hypertrophy, where the joints become enlarged due to chronic stress, leading to localized lower back pain and stiffness. However, unlike cases involving radiculopathy, facet syndrome does not typically cause radiating nerve pain (Kumar 2019).

Treatment for facet syndrome and lumbar spondylosis often overlaps, including physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, and posture correction. Additionally, liposomal curcumin, due to its potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, may help reduce facet joint inflammation and improve mobility (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Can M47.816 Lead to Spinal Stenosis?

Yes, M47.816 (lumbar spondylosis without myelopathy or radiculopathy) can potentially progress to spinal stenosis, a condition where the spinal canal narrows and compresses the nerves. This occurs when degenerative changes, such as bone spur formation, ligament thickening, or disc bulging, begin to encroach on the spinal canal (Kumar 2019).

While M47.816 does not initially involve nerve compression, if left unmanaged, it may contribute to the gradual narrowing of the spinal canal, leading to symptoms such as:

- Neurogenic claudication – pain, weakness, or numbness in the legs while walking.

- Limited mobility and increased fall risk due to nerve-related instability.

- Persistent lower back pain that worsens with standing or prolonged activity.

Early preventive strategies, including regular exercise, weight management, and the use of anti-inflammatory supplements like liposomal curcumin, may help slow the progression of lumbar spondylosis and reduce the risk of developing spinal stenosis (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

What Are the Long-Term Complications of Lumbar Spondylosis?

If left untreated, lumbar spondylosis (M47.816) can lead to several long-term complications, affecting spinal function and quality of life. Some potential complications include:

- Chronic Lower Back Pain: Over time, cartilage loss, joint inflammation, and disc degeneration can contribute to persistent lower back pain, which may require long-term pain management strategies (Kumar 2019).

- Reduced Mobility & Stiffness: As the condition progresses, spinal flexibility diminishes, making daily movements like bending, twisting, or prolonged sitting increasingly difficult.

- Spinal Instability: Severe degeneration may weaken the vertebral column, increasing the risk of spondylolisthesis, where one vertebra shifts forward over another.

- Increased Risk of Radiculopathy or Myelopathy: Although M47.816 does not initially involve nerve compression, progressive degeneration may lead to nerve root impingement (radiculopathy) or spinal cord compression (myelopathy), causing radiating pain, numbness, and motor dysfunction (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

To minimize these risks, maintaining spinal health through physical therapy, proper posture, and dietary supplements such as liposomal curcumin may help reduce inflammation and slow disease progression (Kumar 2019).

What Exercises Help Manage M47.816?

Regular targeted exercises can significantly improve symptoms of M47.816, enhancing spinal mobility, core strength, and pain relief. Some of the most effective exercises include:

1. Stretching Exercises:

- Pelvic Tilts: Helps maintain spinal mobility and strengthen the lower back.

- Cat-Cow Stretch: Improves spinal flexibility and relieves stiffness.

- Hamstring Stretches: Reduces lower back strain by improving posterior chain flexibility.

2. Core Strengthening Exercises:

- Bridges: Strengthens the lower back and glute muscles, reducing stress on the spine.

- Planks: Builds core stability, which supports the lumbar vertebrae.

- Superman Pose: Targets spinal extensors, improving posture and back endurance.

3. Low-Impact Aerobic Activities:

- Swimming and Water Therapy: Provides resistance training without spinal compression, making it ideal for individuals with spondylosis.

- Walking: Helps maintain spinal mobility and overall cardiovascular health without excessive strain.

Incorporating liposomal curcumin supplementation alongside exercise may further aid in reducing inflammation and improving joint function, allowing for better movement and pain management in lumbar spondylosis patients (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

By implementing a well-rounded exercise routine, individuals with M47.816 can experience reduced pain, improved flexibility, and long-term spinal health benefits.

Conclusion

Summary of Key Takeaways

Lumbar spondylosis (M47.816) is a degenerative spinal condition that primarily affects the lower back, leading to chronic pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility. Unlike cases involving radiculopathy or myelopathy, M47.816 does not cause nerve compression or significant neurological deficits. The primary contributors to this condition include aging, genetic predisposition, lifestyle factors, and occupational strain (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Effective management strategies focus on a combination of conservative treatments, including physical therapy, posture correction, pain management, and lifestyle modifications. Interventional procedures like corticosteroid injections and radiofrequency ablation may be considered for severe cases, while surgical intervention remains a last resort. Complementary therapies, such as Ayurveda, Siddha medicine, and yoga, have also shown promising results in improving spinal flexibility and reducing pain (Kumar 2019).

Nutritional interventions, including liposomal curcumin supplementation, may aid in reducing inflammation and supporting spinal health, given its high bioavailability and anti-inflammatory properties (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

Emphasis on Early Management and Preventive Care

Early intervention is key to managing lumbar spondylosis effectively. Identifying symptoms early, making ergonomic adjustments, and maintaining a physically active lifestyle can prevent the progression of spinal degeneration. Patients are encouraged to:

- Engage in core-strengthening exercises to support spinal stability.

- Adopt proper workplace ergonomics to minimize strain on the lumbar spine.

- Maintain a balanced diet rich in anti-inflammatory nutrients such as Omega-3s, Vitamin D, and liposomal curcumin (Kumar 2019).

Regular medical check-ups and imaging tests can help track degenerative changes, allowing for timely interventions to slow progression and improve quality of life.

Future Directions for Research in Lumbar Spondylosis Treatment

Research into lumbar spondylosis treatment continues to evolve, with a growing focus on:

- Regenerative Medicine: Studies exploring stem cell therapy, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and tissue engineering aim to promote spinal disc regeneration and cartilage repair.

- Advanced Minimally Invasive Procedures: Innovations in robotic-assisted spinal surgery and laser disc decompression offer safer, more precise treatment options for advanced cases of lumbar degeneration.

- Natural Anti-Inflammatory Therapies: The role of liposomal curcumin and other bioactive compounds in managing chronic inflammation and oxidative stress is an emerging field of study that could provide non-pharmacological pain relief (Kulkarni and Parwe 2024).

- Personalized Treatment Approaches: Future research is likely to focus on genetic predisposition and lifestyle factors, leading to customized treatment plans tailored to individual risk factors and disease progression (Kumar 2019).

By integrating modern medical advancements with preventive care and holistic therapies, individuals with M47.816 lumbar spondylosis can achieve better long-term outcomes and improved spinal health.

References

Sources Cited in the Article

- Kulkarni, S., and Parwe, S. “Ayurvedic Management of Lumbar Spondylosis: A Case Study.” International Journal of Ayurveda and Pharma Research, vol. 12, no. 3, 2024, pp. 45-52.

- Kumar, M. N., Deepika, and Poongodi Kanthimathi. “The Effect of Yogic Practices and Siddha Treatments for Lumbar Spondylosis: A Case Report.” International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences, vol. 8, no. 5, 2019, pp. 183-186.

- Kadhim, M., et al. “Role of Physiotherapy and Exercise Therapy in Managing Chronic Lower Back Pain Associated with Lumbar Spondylosis.” Journal of Musculoskeletal Research, vol. 10, no. 2, 2021, pp. 78-92.

- Natarajan, M. V. Natarajan’s Textbook of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 8th ed., Wolters Kluwer, 2018.

- Gore, M. “Treatment of Disease through Yoga.” Sports Publication, 2011, pp. 198-202.

- Vinayakumar, A. Ayurveda and Yoga. Sri Satguru Publication, 2012.

- Tekur, Padmini, et al. “Effect of Yoga on Quality of Life of Chronic Lower Back Pain Patients: A Randomized Control Study.” International Journal of Yoga, vol. 3, no. 1, 2017, pp. 22-29.

- Mahadevan, L., et al. Handbook of Siddha Clinical Practice: Neurology and Rheumatology Based on Tridosha Concepts. Sarada Mahadeva Iyer Ayurvedic Educational and Charitable Trust, 2011.

- Shanmugavelu, R. Principles of Diagnosis in Siddha Medicine. Department of Indian Medicine and Homeopathy, 2009.

ALSO READ: Liposomal Curcumin – Benefits, Uses, and Scientific Insights